The synth elements on almost all of Sleeping Giant are extremely subdued. This massive track is more ethnically influenced than electronically, with some random delay effects on Hancock’s playing spacing things out every so often. He lays out modal chords for 30 seconds to minutes at a time, freely improving upon them in ways that often don’t harmonically match up. This track needs to be broken up to be analyzed accurately.

0:00-2:30 is mostly introduction and building of tension through ethnic percussion

2:30- 7:30 we get a taste of our first theme, a groove that drops in and out between Hancock’s solos

at 7:30 we hear the most cohesive “chorus” on this entire track. A few strung out bass notes and slow clashing chords from the electric piano. This builds into a gushing major ballad with harmonized horn and sax. Henderson has an excellent airy tone on this album, like baby’s humming.

at 11:00 we’re back into groove mode; this time driven by some blusey piano echoed by wah wahed keyboard. They repeat the same notes verbatim for over a minute. It’s cool though, and we get some transcendent waves blasting from the Moog as we’re taken into darker territory. It mimics the transition a bit from 7:30 and then jumps into a new groove at 14:00. This time we get more funky with a bass guitar line and some shakers and muted cowbell adding texture in the background.

Around 17:00 we call back to that uneasy transitional chorus, this time with a delayed sax solo.

18:30 gives us a theme remarkably similar to the ethnic one we started things with (recapitulation?). Finally there is just enough time to hear one more eerie slow section, which ends with more of a sultry feel as the wind instruments play up and down the first few steps of a minor scale.

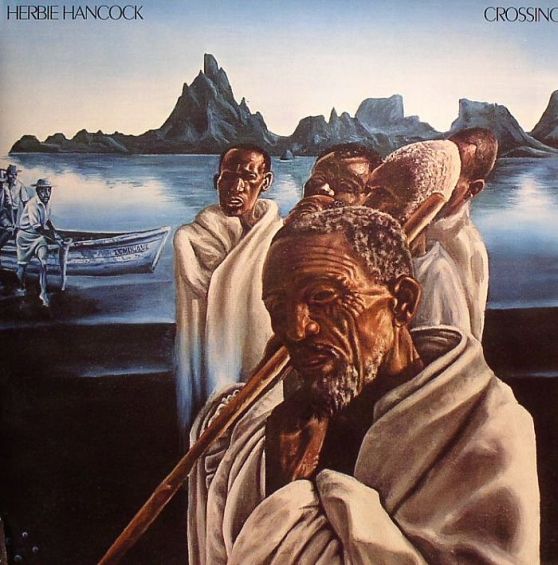

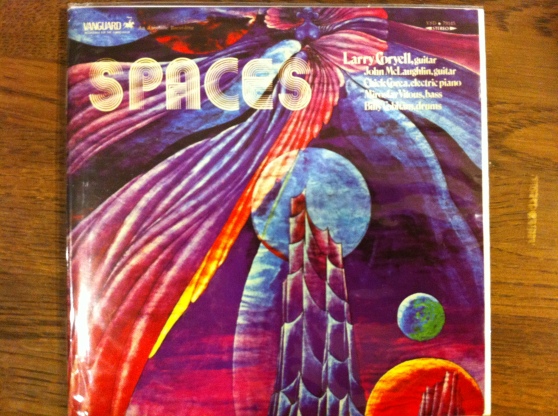

It’s a great track and I’ve listened to it about a dozen times the past week or so. I’m still trying to decide if it was actually necessary to leave it at such an unwieldy length instead of splitting it up. There was obviously a good deal of composition done on it, so it wasn’t just a jam session gone wrong. I’ve been looking at the cover, imagining a river crossing, and trying to think of the story Sleeping Giant tells in that universe. This thing is damn near sonata form and it deserves some kind of liner notes explaining more about its goal.

Quasar was written by Bennie Maupin, the sax and clarinet player on Bitches Brew. This thing is from a future we have not yet reached. Flawless basslines, luscious Rhodes chords and flute played in harmony, and incredible synth lines from Gleeson on the Moog.

If you’re not aware of Patrick Gleeson, he played on a few Elektra and Prestige records in the 70s and 80s as well as designing soundtracks for some notable movies from the era. Originally he was just going to set up the Moog for Herbie but then H heard his playing and wanted him on the record in person. The uneasy high fluttering and low wobble he coaxes from his synth were probably completely alien to a lot of the listeners of this record in 1972. Groundbreaking track, and more electronically advanced than anything we had heard from Miles up until this year.

Water Torture is also very good but I think it is hard to outclass Quasar. Overall this record has the same sensibilities as Mwandishi but it is more technically advanced and arguably contains better writing. This is probably one of the most important albums of the era, and you can tell the Moog is still kind of seen as more of a trick than an actual instrument. When the musicians finally let it steal some of the spotlight some completely incredible moments are created.

Crossings gets 9/10 Quasars (is that some kind of interstellar currency?) Sleeping Giant indeed.